Historical Setting: 789 C.E. Jutland

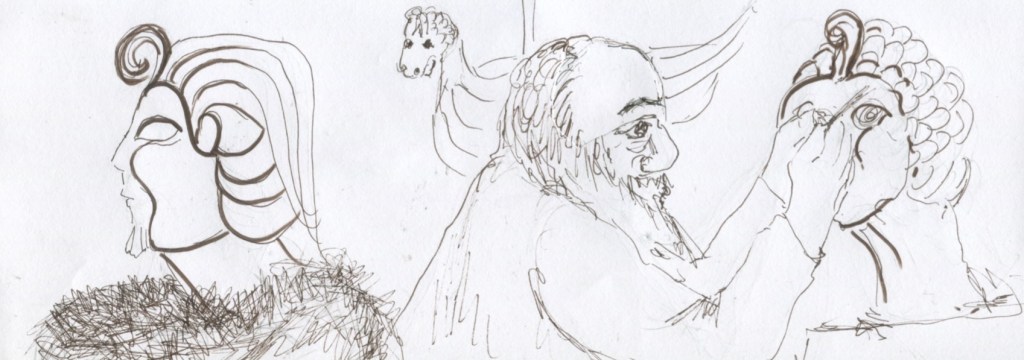

The elder woodcarver is complaining about the erroneous carving by a younger smiðr which was prepared for the new ship being built. The elder brought the failed art back to his own work table to “fix it.” He will have to magically shape-change this thing into a properly ferocious dragon. When he removes the bear skin, unveiling the art, it is very clearly a fine carving, but not of a toothy, scaly, dragon’s head. It is a regal and all-powerful head of an Egyptian Sphinx.[Footnote]

Apparently, the younger smiðr assigned to this artwork is a well-seasoned world traveler. And the elder art critic only values local dragons and sea monsters. So maybe it is sometimes possible that tradition demands shape-changing.

The old man sets the head with a Pharoh’s face onto his work stand, not even imagining the lion’s body with outstretched paws needed to transform a boat into a rightful sphinx. He might have missed the point of the mythical hybrid altogether, because clearly this thing he calls tradition does not flex for exotic foreign creatures. He flicks his chisels on the whetstone and taps away at the nemes (or Pharoh’s striped cloth) changing the stripes to scales, cut deep, in a staggered pattern, row upon row of perfect dragon scales.

Marian, as young as she is, believes she also knows the power of tradition. The wrangling over her as a slave, empowered her belief that it is tradition that gives a person value – even a slave. At least tradition, drawn from some other time or place where she was raised before capture, seems to be what gives utility to her person. She found that knowing the tradition of baking bread has become her bargaining chip. But she doesn’t get the coins for the bread. And that pittance of coins that were argued over is the price of the slave who bakes the bread. Maybe, only in the mind of a ten-year-old, lost and grieving for her family, desperate to belong somewhere, is the price offered for the tradition she remembers worth the total value declared for her humanity. It is a grieving child’s perspective.

I ask her, “Is it different for you now that a price was asked to make you into a bought slave?”

“You make it sound like a bad thing.”

“Are you allowed to make your own choices, or must you only do what a slave does?”

She laughs, “I’m a child. I do what I’m told.”

[Footnote] This element of a ship’s carved head is fiction here. What is sustainable history is that the trade routes through the Baltic and beyond were vast and included Egypt and areas to the east.

(Continues tomorrow)