Historical Setting: 793 C.E. Lindisfarne

Visiting dignitaries becomes a procession of mourners as each visitor must ponder his own mortality and the fragility of life. Some here count the years until the charted end of the world – Doomsday – scheduled at the end of this millennium. There is the personal hope that this tragedy was only about the sin of the monastery, and not really about God’s Day of judgement. But truth be known, only the brashest of lies can argue these deaths are blamed on the burial of one sinning novitiate. The blatant liars of the political realm hope the bishop will take the blame for this because some believe the Viking attack was due to the late abbot’s decision to bury that sinful novice as though he were a rightful monk.

The bishop brings the letter from the acclaimed scholar Alcuin, which I already know lays the blame on everyone. Seeing the use of this letter Alcuin’s groping for sin and blame makes sense. These survivors need a reason.

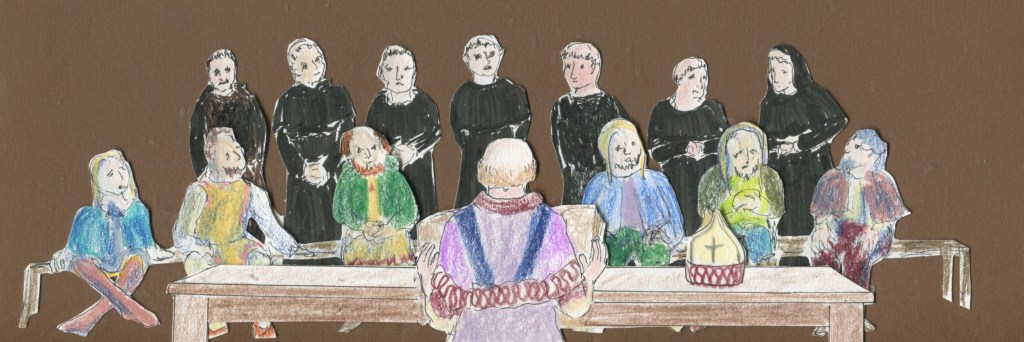

Benches are arranged for seating because, apparently, the bishop plans to fill the hours until the next low tide for crossing back to the mainland, with his sermon. Higbald rises to speak behind the naked table, striped, as it has been, of liturgical cloths. He calls for all to stand for the reading of the gospel as he lays opened Lindisfarne’s true treasure, with the outer covers spread face down on the bare wood. Turning to the carpet page before Matthew, created here by the hand of a beloved monk, perhaps inking the images at this very table.

The bishop is silenced for this moment with the awe of the book. We’ve all seen these facing pages. We know this art, and we have felt the awe ourselves. We stand in holy silence knowing of the images he sees, the cross made of six connecting partial circles, with the one a perfect circle at the center, all amid a sea of vipers in their intricate patterns of coils and tail grabs.

Opposite that page is the beginning. The first letter, one form with three heads and each head is starring at us. [Footnote]

Having spent my hours while the squash soup simmers, waiting at this altar, mesmerized by this work of art, I am indeed an iconodule. I am grateful for the artist who, in the true image of Creator, illustrated amazement with creation for our human eyes to see.

[Footnote]Eleanor Jackson, author of The Lindisfarne Gospels: Art, History and Inspiration, The British Library Guide, provided a beautiful description, of “each incipit page… surrounded by a frame which seems not to contain the letters so much as retreat from them, allowing them to burst out of the top and escape through a gap in the lower right. With their apparent ability to metamorphose, expand, contract, progress and interact, the letters seem to be living beings, reminiscent of the interlaced and contorted creatures that are so prominent in the decoration.” p.59.

(Continues tomorrow)