Historical Setting: Jarrow, 793 C.E.

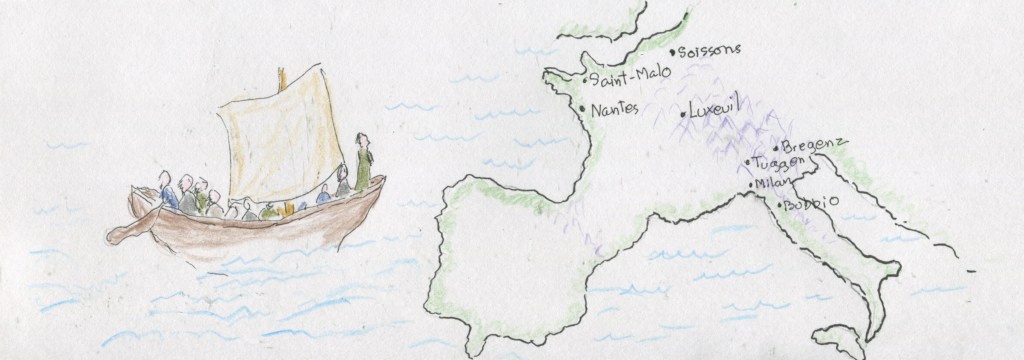

I have a personal stake in this history, because, in all my years, I’ve felt the sense of belonging in monastic communities before there was a Benedictine Rule at Tours and at Ligugé. Then my need for community for sharing faith was met with the Irish missionary, Columbanus, who eventually established eight monasteries throughout Burgandy and the Italian Alps.

St. Columbanus finally accepted the Benedictine tonsure and the Roman Rule for the Easter date as a concession for the blending of rules to include things that he felt were more essential to the depths of faith than hairstyle. For example, for Columbanus, obedience to God was first and foremost, over the obedience to the human hierarchy of Church.

This is where the time-freeze of Bede’s writing frustrates me. In a world where scribes and authors pay homage to saints with fantastic stories of miracles and signs, the historical record of political controversies also becomes tainted with subjective opinions. I call them subjective opinions, but when an opinion is accepted as fact, even wars can arise over seemingly meaningless differences. Opinion serves people better in debate where all sides are said with the fulcrum of the balance posting the resolution.

Bede mentions the Arian controversy, not a controversy in these times. It was said to be settled once and for all at the Council of Nicaea in 325 when it was made official that God came in three parts. Trinity perfectly suited Christians, newly received from paganism where many gods do seem to rule. It also offered a decisive explanation made of functional human words, which, to the rising earthly emperor, Constantine, was a perfectly reasonable way to explain an invisible God with an unspeakable name.

Well, actually it was settled again and again and not really once and for all even at the Council of Chalcedon in 451, when nuances of the relationship of “Father” and “Son” seemed a worthy reason for clobbering unbelievers with wars. The wrong-headed, or losers in the wars that followed, divided people who were all nurtured in the teachings of Jesus, into the righteous and the flat-out wrong. Arians were the wrong, because they followed the wrong guy at the Council of Nicaea, and Arians didn’t accept the interpretation ruled by the “one universal Church.” Arians were anathema, and viewed as worse than pagan. Since it was the Church that owned the vellum, the Church’s edicts of righteousness became facts of history.

(Continues Tuesday, November 11)

There were certainly grievous sins in the way the institutional church dealt w/ heretics. But it was attempting to combat heresy, which is a limited truth distorted into a misleading whole. That cannot be overlooked.

LikeLike

Yes. The heresies and the human judgments over different perceptions and misunderstandings have fed hatred and wars for centuries. As humankind becomes more aware of broader diversity may we learn the wider acceptance of the many varieties of holy relationship — possibly that God loves all people. By noticing the metaphor of Creation, it can be observed that God appreciates diversity, yet tolerance of ideas is a lagging lesson, especially tragic when intolerance is based on lies.

LikeLike