Historical Setting: 793 C.E. Jutland

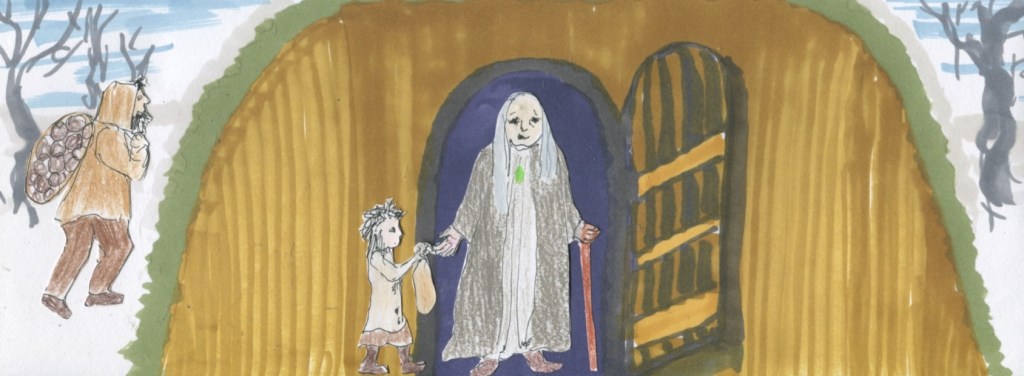

I knock on the door and the elder comes from behind the house with her cloak and bag, a skin of wine and walking stick prepared for a journey.

I know enough words to understand, “Let’s walk together so we may hear one another’s long stories.”

“Where will we find the meanings for words?”

She answers in my own language, “We tried a translator who wouldn’t tell me what you said when you told me you are old and have a long memory. And I wanted to know more from you.”

“How is it you know my language?”

“Only the words change with time and place, language is the same” –undoubtedly one of her riddles for which she is known.

We are walking north along the shore seeing more of these boats.

She answers the language question again, but now with earthly clarity, “We have boats. We visit all of the distant lands for trade. We have to deal with the languages of others and all the oddities and verbosities of communication.”

“I noticed your brooch of jade, depicting an eastern dragon.”

“So, you have a good eye. It’s a very long journey to that eastern land, but the trade isn’t complicated—simply gem for gem, metal for metal, art for art, word for word. It doesn’t require portraits of Romans or Kings hammered in gold to force the fairness of trade. But this one was my mother’s.”

“Really Your mother had this?”

“I didn’t know her. She was probably a thrall. But here gems are traded for amber and amber is often found just across the sea. There begins the amber road for trade to all the lands east.”

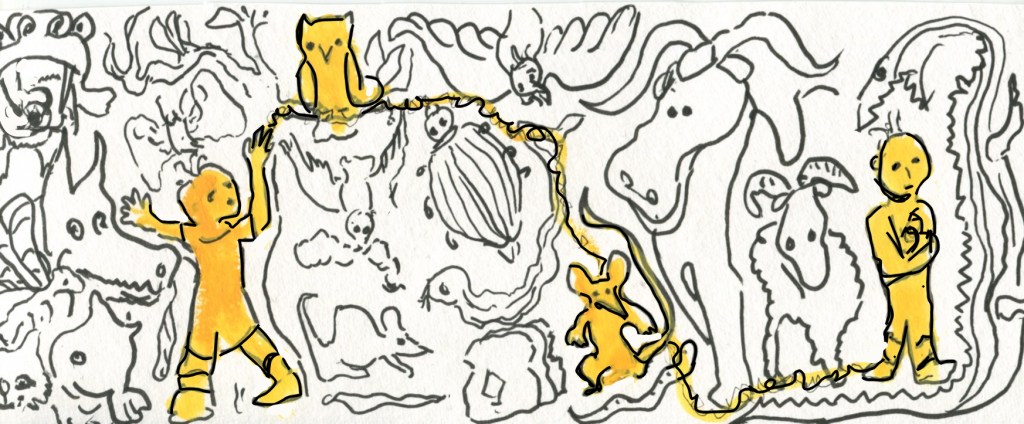

“So, the hard amber that once oozed from a tree is precious enough to trade for jade?”

“Of course, amber is precious because it keeps what once was. Sometimes that is pure and clear, but sometimes it holds a memory of a life in a more ancient time. Then if a living stranger shows up among us, claiming he is what went before, speaking the old language of the northern edge of Gaul, any seiðr would want to hear what he has to say; it’s like finding a dragon fly in amber. When the child thrall knows of the oddity of him she just chooses not to translate, so I’ll have to hear it myself.”

“If it eases your curiosity, I did once see aurochs.”

“So you, like the dragonfly in the amber, are a visitor to us from another time?”

(Continues tomorrow)