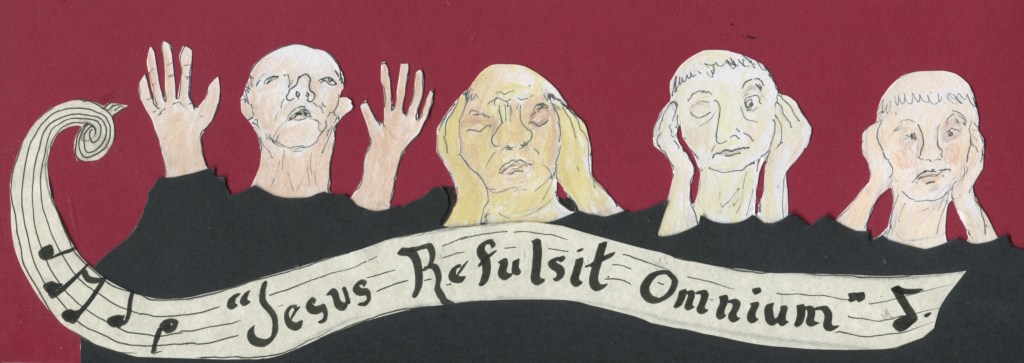

Historical Setting: Jarrow, 794 C.E.

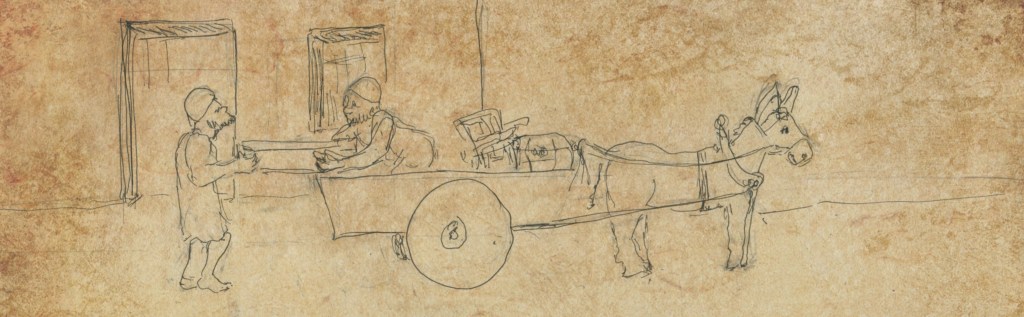

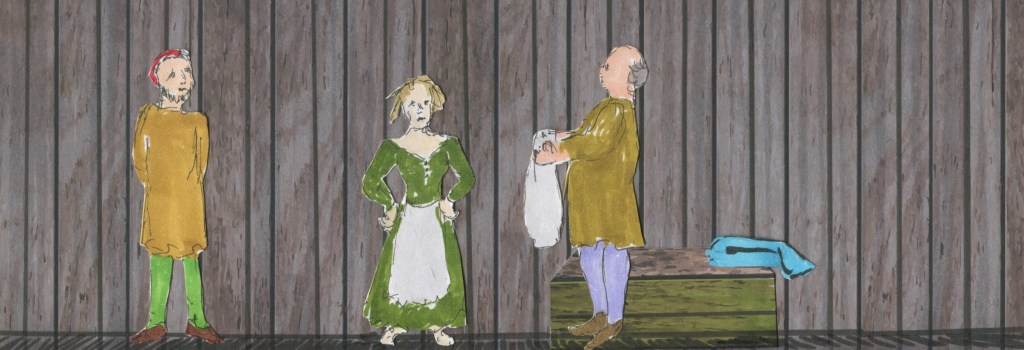

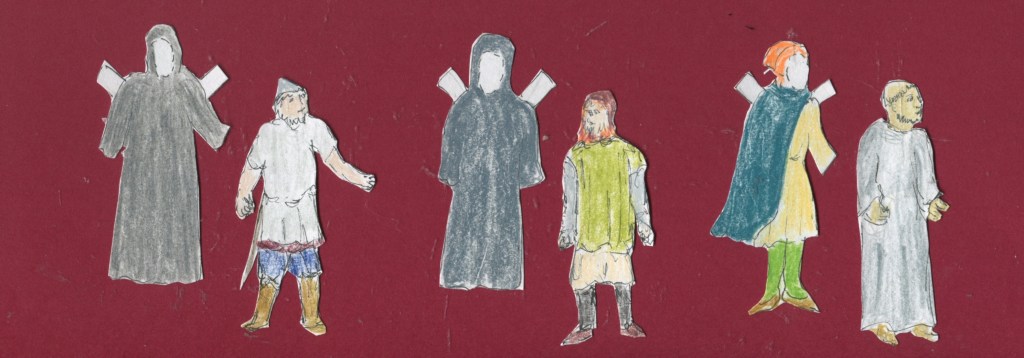

Ousbert finished emptying the ealdormen’s house and now his men have left with the full cart of the squandered and pilfered remnants of his loveless evil. All the people’s losses were the shabby little treasures that this ealdorman had collected from people seeking justice in their times of hardship.

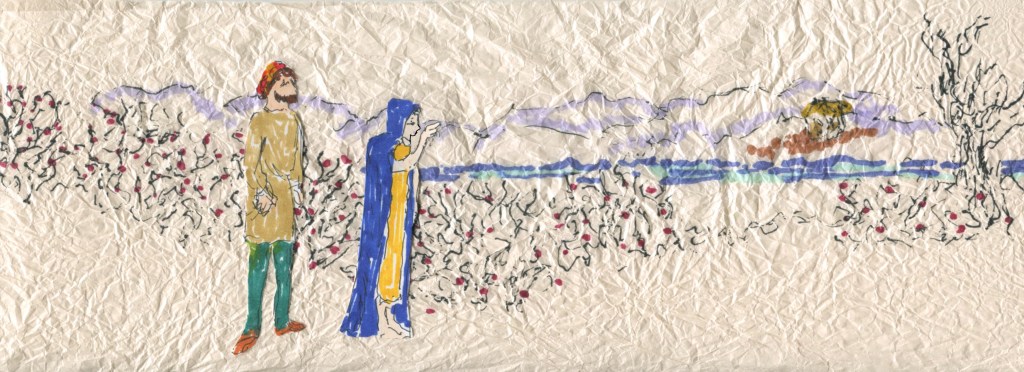

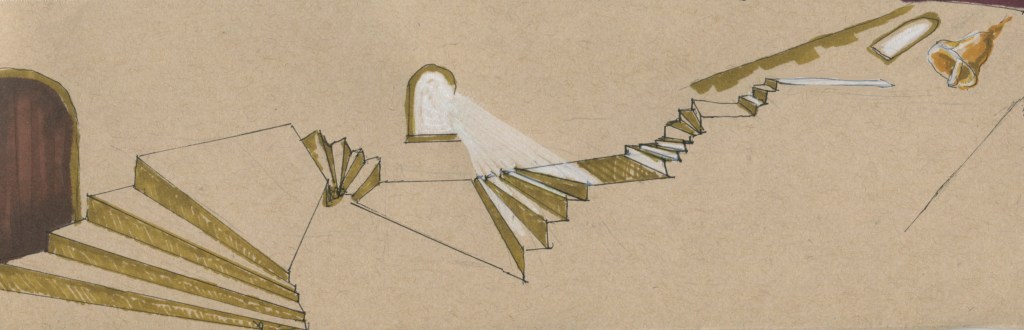

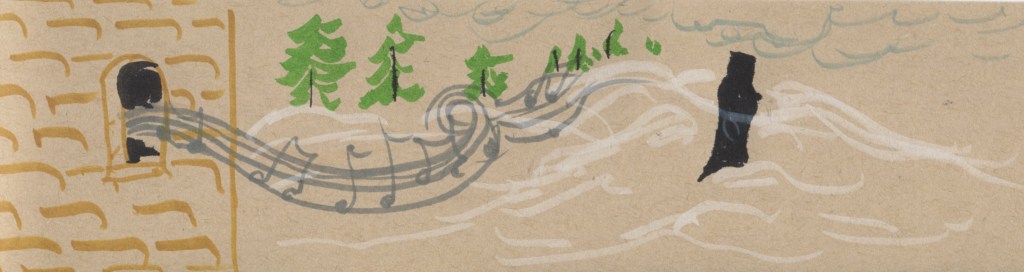

It is getting dark and I need to return to St. Paul. Ousbert is staying there also so we walk together with the light of his lantern revealing only the next step before us and only as we need it. Empathy gnaws for the wrongs done to the people here by their own protector, this ealdorman.

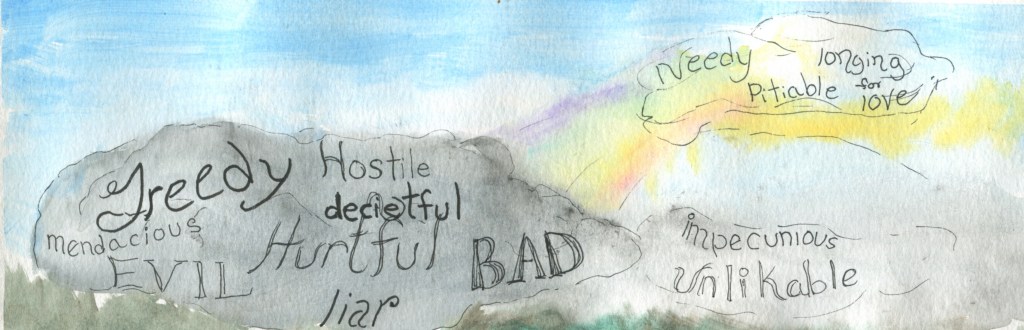

Evil is reality even on God’s love-born earth. It isn’t a demon, to be exorcized by holy magic and driven into the sea. And it is a different neediness than the cold and hunger of poverty that can be resolved with empathetic generosity.

Evil is the greed that occupies the hollow place in spirit which was once a child’s longing for love. True evil is the warp of the golden lie of greed, empowered to obscure love’s healing power. It is as impossible for a rich man to enter that kingdom as it is for a camel to go through the eye of a needle. I didn’t just think that up. [Mark 10:25]

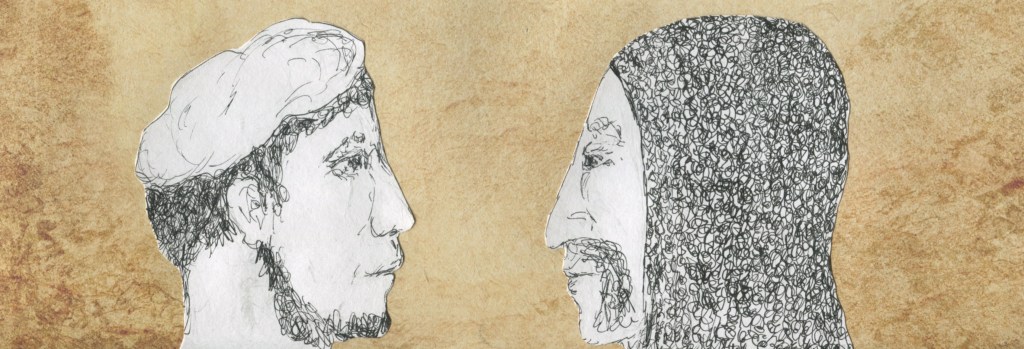

Ousbert and I stumble through the darkness with no words spoken. We are both mulling in silence all that was revealed in that log book until Ousbert breaks the silence.

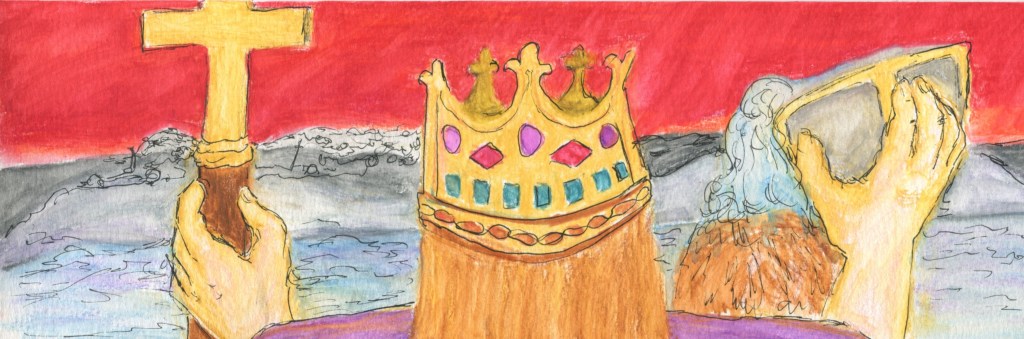

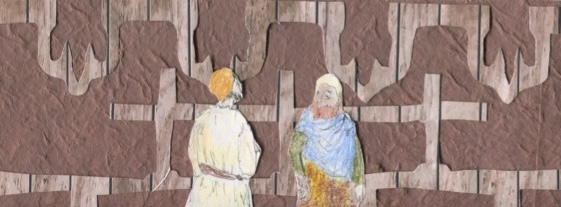

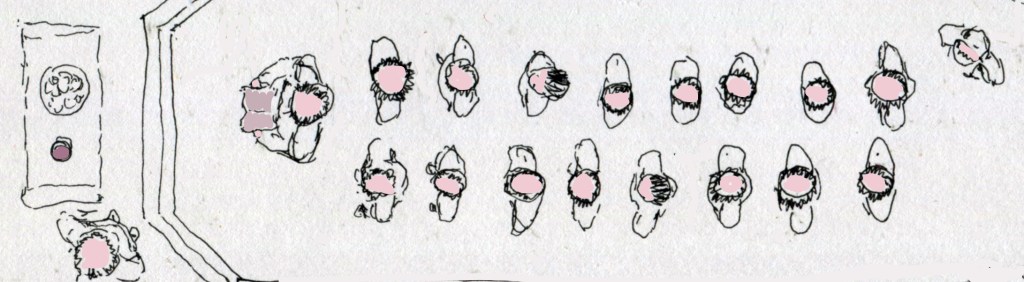

“When I came with soldiers to take that ealdorman away the people came out of these houses and hovels thanking me. I told them we were only taking him to appear before the king. The king would need to rule justly. I’m not even sure that King Ethelred can rule justly. He, himself, may believe mere power makes one impervious to evil.”

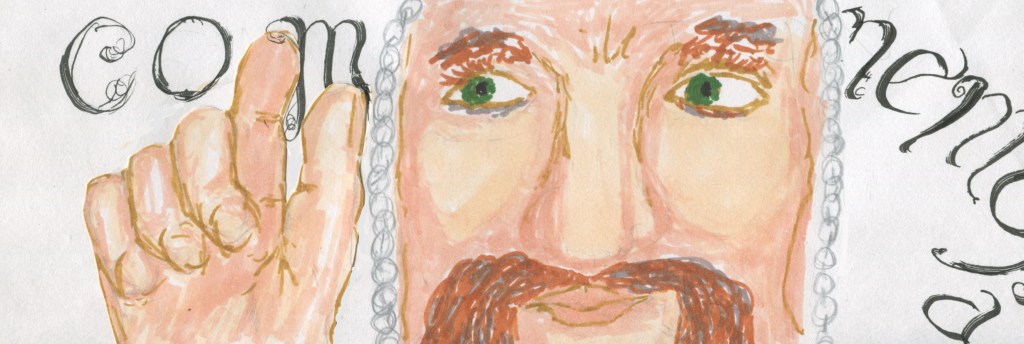

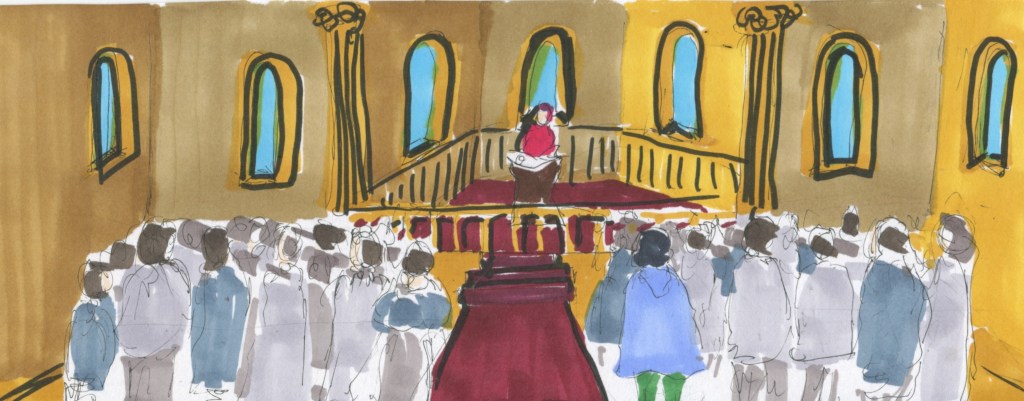

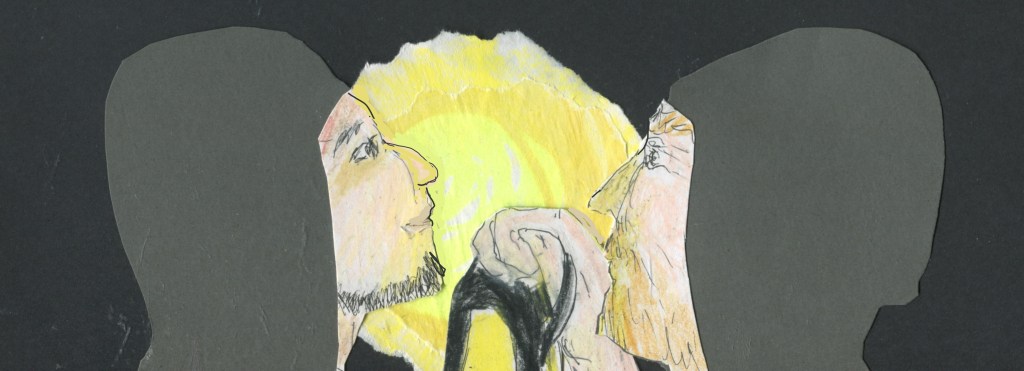

“I know when we prepared that vellum page to unfurl at his court, you were concerned over the appearance of the page, saying that the look of it mattered more than the truth of it.”

“I never trust this king to have empathy for the poor, so the commendation had to have the lovely appearance, regardless of the truth of the story.”

“And you still think if the document had simply been jotted roughly on a cleanly scraped piece of parchment the king wouldn’t have cared about the heroic rescue of the girl from the sea?”

He smirks.

“The people trust the king to rule justly. But I am the king’s man. I’ve seen things.”

(Continues tomorrow)