Historical Setting: Jarrow, 794 C.E.

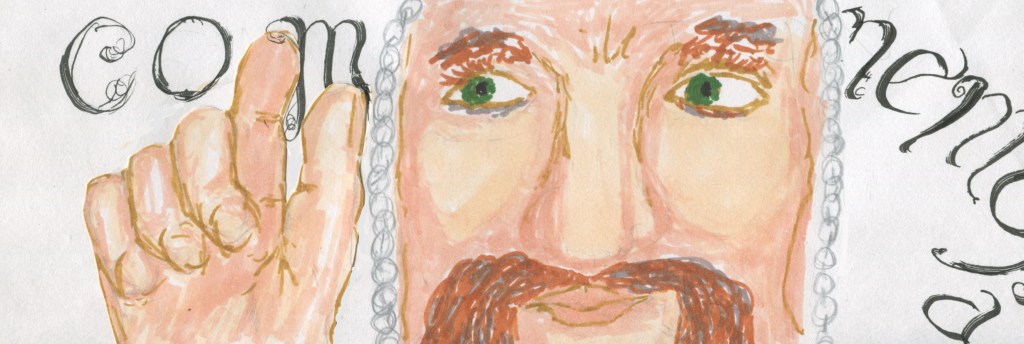

Ousbert, the king’s man who oversees the guarding of Jarrow against the Vikings is asking me to do the abbot’s or an ealdorman’s job of writing a report to the king. He wants a letter that will make a fine display before the court and that has good words commending the guards he has placed on duty here. He tells me something I already knew of the ealdorman, though I have only heard stories. The ealdorman here is known to be a cruel and self-centered fellow, who would prepare the letter putting himself in the role of the one who assigned the guards in making all these preparations for a Viking raid.

“So, it isn’t the abbot’s letter you would have me write. It is the letter from the ealdorman.”

“It will have my name and my seal.” says Ousbert.

He mentions payment, and I could buy my cloak back from Cloother with that coin. And also, I would like an opportunity to inform the king about the unfair treatment of a pauper by this very same ealdorman excluded from this assignment.

So, “Might this commendation of the guards also include a denunciation of the ealdorman?”

“What are you thinking?”

“Maybe just an explanation after the signature like, ‘Ousbert, in leu of the local ealdorman.’ Then a note could be added in smaller letters, of course, than the commendations, that would give examples of the ealdorman flaunting of his power over his district.”

“You have examples?”

“I’ve heard a story of it.”

So, I tell Ousbert all that I know of a woman rescued from the sea by these royal guardsmen who are being commended.

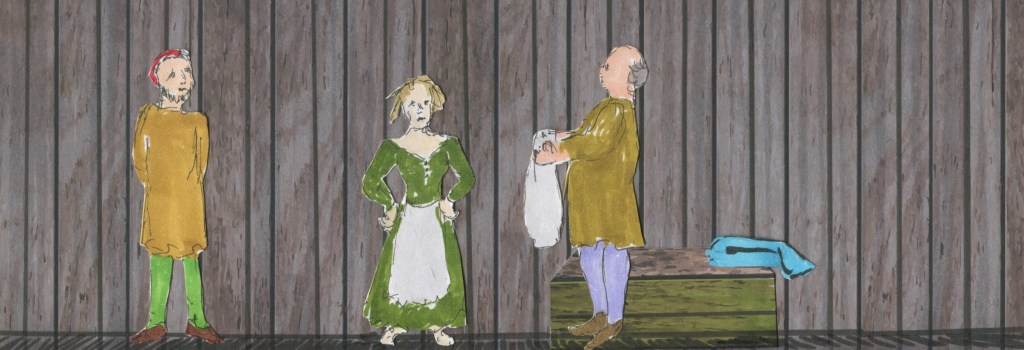

“Yes!” He says, “This is very useful! Might we find this woman again, and dress her up in courtly gowns to go before the king to tell her own story explaining why justice isn’t available from the cruel ealdorman.”

I fear I’ve said too much. He was just looking for an excuse to replace the ealdorman, perhaps with himself, and now I’ve put the troubled young girl in the midst of their own power play. And not only that, I can imagine her audience with the king, outfitted as a perfect stereotype of a helpless waif, that will end with her being dragged from court, howling curses at the king. She does have that strong core of self-reliance and she has very little regard for glitzy powerful rule makers.

(Continues Tuesday, February 17, 2026)