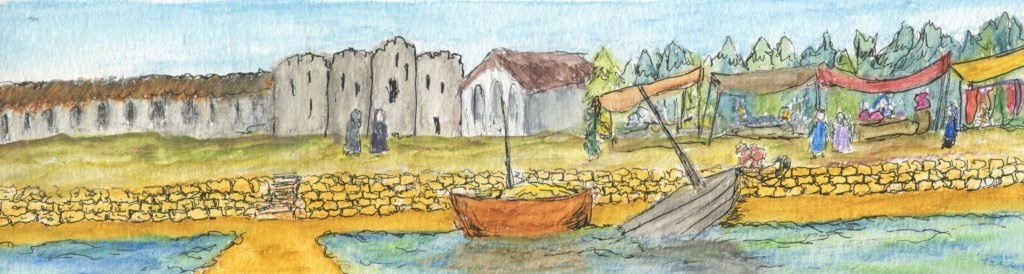

Historical Setting: Jarrow, 793 C.E.

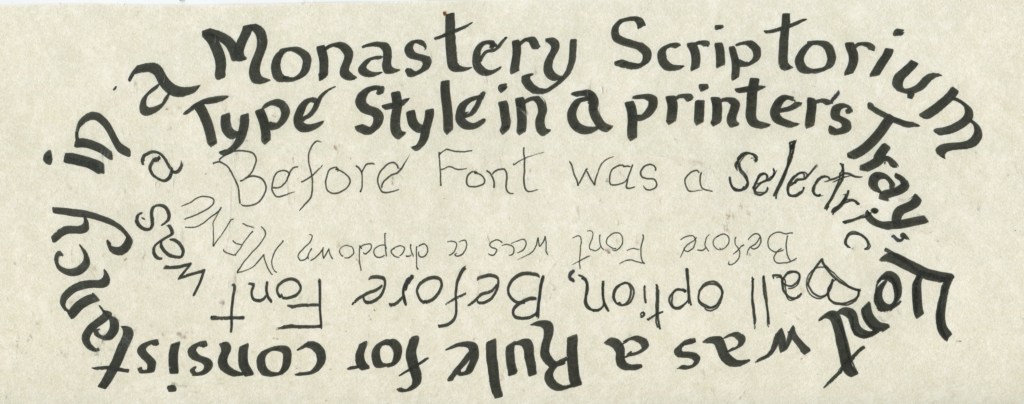

Apparently, my simple sentence of purpose in the librarian’s log book reveals my long past connection with Luxeuil. What I thought was standard manuscript lettering is now only one of several styles used by monks. The style of lettering used can reveal when and where a manuscript was copied so my flourishes and downstrokes belie my Merovingian years, and the spread of the ink reveals my time as a follower of Father Columbanus.

As I explore the books on these shelves at Jarrow, I see there are several different manuscript styles and the style used by the monks here spaces the letters apart more for a simpler clarity, fewer down-strokes tapering off below the line all clean and simple but with beautiful curves, making for faster reading and faster copying. That may explain this vast collection of books here and multiples of the books this monastery is known to have inspired at Bede’s hand.

I first asked for the book The Ecclesiastical History of the English People by the Venerable Bede. [Footnote] That’s the book that brought me here.

The old librarian says, “Copies of the sixty-two-year-old text are here to be read by anyone using this library.”

I place the book on a reading stand, and I am preparing to fill the curious little place in my wondering with a whole new history of things. It is a blessing not to have to learn about this land in these times through an interpreter reading runes chipped in stone.

I see, in Bede’s list of chapters of this Book 1, that this history begins with the Roman emperors.

Old Wilbert interrupts before I even read the list of chapters and he asks me to sit with him at the table in a private room.

“So, Eleazar, it is good to see a student, who, by his own accord, chooses to read this work by my own teacher and spiritual guide.”

“You knew Saint Bede in his lifetime?”

“I did. When he was very old and speaking his last, I was the one privileged to be the scribe at his side.”

“He was prolific I see by this vast collection of his works.”

“And he always worked in the company of angels.”

“As I supposed. How did you meet him?”

“Like Bede himself, I was brought to the double monastery as a young child. He was only seven years old when he was delivered here for his education.”

“Is it usual for children to be left here?”

“Only as God commands it.”

[Footnote ]Bede, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, The Greater Chronicle, Bede’s Letter to Egbert is still available for anyone to read in modern English through Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford University Press, Rev. 2008, edited with an Introduction and Notes by Judith McClure and Roger Collins. No monks with quill, inks and parchment were needed for this blogger to have this opportunity to read it, thankful for the gifts of 2025.

(Continues tomorrow)