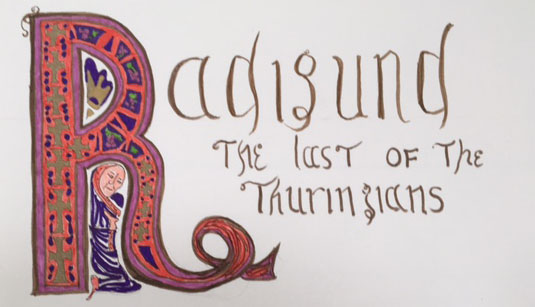

Historical setting: 584 C.E. Ligugè

Brother August is telling me about the double monastery now called the Abby of the Holy Cross.

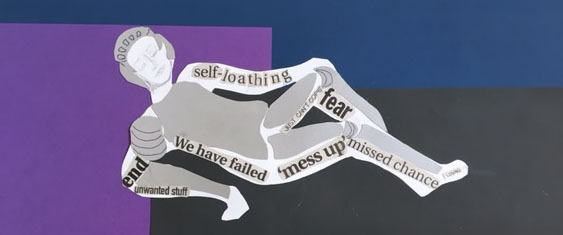

August explains, “While I was in the infirmary some of the nuns assigned to patient care were always whispering among themselves about how they were mistreated by the strict rule of the order. The Rule for Virgins, (Regula virginum (512), [Footnote] was designed by a man of power many years ago, Caesarius of Arles. He was thinking that Rule was to be followed by his own sister, Caesaria. Apparently she had worse sibling trouble than I did. You can imagine the structure of any Rule for Virgins designed by a man who also had a severe passion for order. It required the cloistering of the women. Once they were in the convent they could never leave. This rule defining all of their hours and days is infinitesimally explicit.”

My observation, “It’s like all of those rules made in the time when the Church clings to the last thread of imperial power dangling into the empty pit of warring barbarians. It seems a futile grasp at the waning Roman order.”

Brother August adds, “These sisters serving there were definitely feeling stifled by the rule and apparently not the least bit spiritually inspired by it. I asked them how they could know God’s love under these circumstances. One told me she thought the only thing that brought her close to God was that they could be helpful in people’s healings.”

“And there you were, your life in their hands. Wouldn’t you just pray their answer would have to be some version of Christian compassion?”

“Yes, of course. But I wasn’t expecting so much honesty. I mean, how would they know I wasn’t a God-spy, or an angel reporting their bad attitude directly to God. They can deny liking the Rule, but the ultimate evil would be denying the love of God.”

My assessment, “It seems no matter how thick the walls of cloister and firm the orders of human judgment a smidge of holy empathy always seems to break through. I’m glad the nuns were there for you with kindness.”

“Thanks, Brother Lazarus. So what of your scars, have you also found the blessings of healing?”

“Healing, yes. But I choose not to make the story of my life about the scars.”

[Footnote] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caesarius_of_Arles (retrieved 4-1-2021)

(Continued Tuesday August 24, 2021)