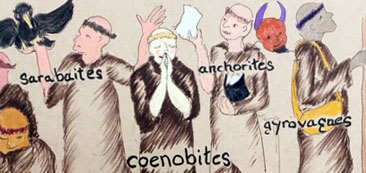

Historical setting: 584 C.E. Ligugè

Changing the subject, I just asked Brother August if The Rule made allowances for an artist who cuts stone.

He answers, “At Ligugè we don’t concern ourselves with The Rule yet the abbot here has been generous in allowing me to continue my prayers with a hammer and chisel in hand.”

“That’s good. I can imagine there would be no room for an artist in all that order and routine of The Rule.”

“Oddly enough, Benedict’s Rule Number 57 [Footnote] would allow for a craftsman to do such work. But The Rule of Benedict isn’t about the works of art, so much as the sin of pride an artist may have. And indeed, pride was my own burden of sin. But The Rule doesn’t address ‘pride’ as something that would intrude into my love for brother with the striving and envy I had been practicing. Rather Benedict’s measure of sinful pride by a craftsman comes in the selling of the art. Apparently, for Benedict, value is only measured outwardly, according to the monetary worth of something. So the artist is not to receive money for the work or The Rule assumes that may lead to pride. In the instance of selling one of my works which Nic purchased from a dealer to bring as a gift to this place, I received nothing for the work but I benefited from the opportunity for a long walk here with Nic and your father. So by The Rule I showed no sin of pride because I received no money.

“Ligugè has been a good home for me all these years, and for Nic also; We added Brother Joel to our numbers but lost your father along the way. Brother Joel was truly a spiritual guide for me in considering my actual sin of pride. Thankfully Joel lived a very long life and his bones are only recently in this graveyard.”

Brother August shows me a marker he made for Brother Joel. On this, Brother August has carved a bird in flight — soaring. It is a perfect image of this elder monk, since Brother Joel’s spirit was always gliding and soaring as a bird. But chiseled into a weighty earthen stone I can also recognize Brother Joel’s awkward paradox of earth and spirit.

“So what did Brother Joel have to say of pride?”

[Footnote 1] White, Carolinne, Translator,The Rule of Benedict, London: Penguin Books, 2008. page 84.

(Continues Tomorrow)