Historical Setting: Jarrow, 793 C.E.

The Lindisfarne raid raised concern throughout the kingdoms for the safety of all of the coastal monasteries. Wilbert introduces me to Ousbert who serves the king as a military advisor. Ousbert has questions about the raid on Lindisfarne. We step out of the library hall, to talk more freely in a gathering place, though here this great hall echoes our conversation into grand pronouncement. It isn’t private.

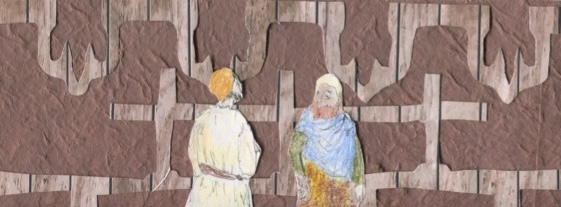

“Brother Wilbert tells me you’ve just come from Lindisfarne.”

“Indeed. I was there at the time of the raid by the Norsemen.”

“The poor fools, holy men, trusting a dead saint to save them. The king wants Northumbria to be better prepared with a force of armed guards to fight back when the Vikings come calling again.”

“I think the monks of Lindisfarne believe they’ve always been well cared for by the Shrine of Cuthbert. But you’re right. I’ve also heard those grumblings that they believe St. Cuthbert should have saved them.”

“So you agree it was Saint that let them down? Or, could it actually have been the monks who lacked military training?”

“Considering the hazards of earthly sins warring could befoul a monk so, for the soul, a saint seems a safer choice.”

“This was a completely different kind of danger for a monk.”

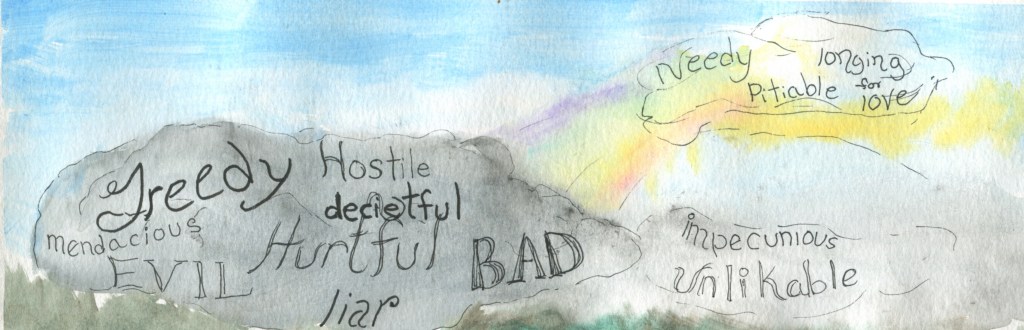

“There is plenty of blame — Alcuin, the scholar blamed sins of drunkenness and greed. Others simply attributed it to the wrath of God.”

He asks, “As one who saw it, what do you think was the cause of it?”

“I think it was the Vikings.”

“Of course, but what caused the Vikings to cause it?”

“It was definitely caused by greed, with a chaser of strong drink. But whose greed and whose drunkenness are to blame? That’s the question. Alcuin was blaming the brothers of Lindisfarne, but honestly, I still lay the blame square on the Vikings. There was plenty of greed and drunkenness among the Vikings. At Lindisfarne, their barrels and kegs were stolen, and their earthly treasures are gone, so any possible continuation of greed or drunkenness at the monastery is null.”

Ousbert says, “As an advisor for the king, my assignment is to prepare the coastal monasteries, Jarrow and Monkwearmouth, so they can save themselves, should there be another attack.”

“Still, preparation for any attack would need to consider the greed and weaknesses of the Vikings. They are, this very hour, trading the treasures of Lindisfarne. This is definitely about greed.”

(Continues tomorrow)