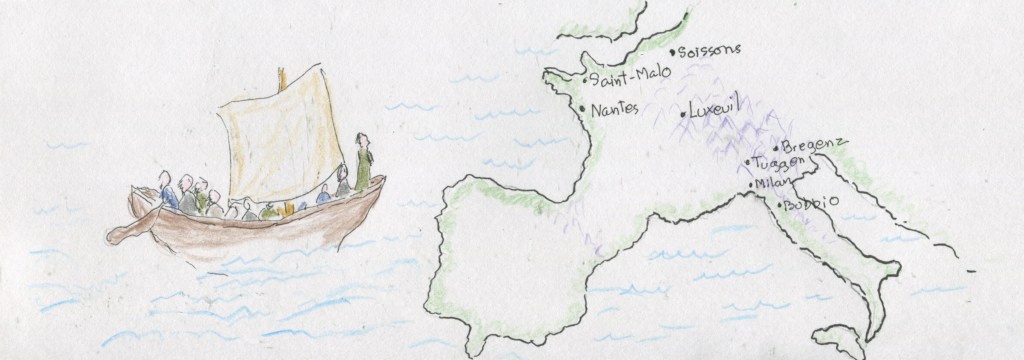

Historical Setting: Jarrow, 793 C.E.

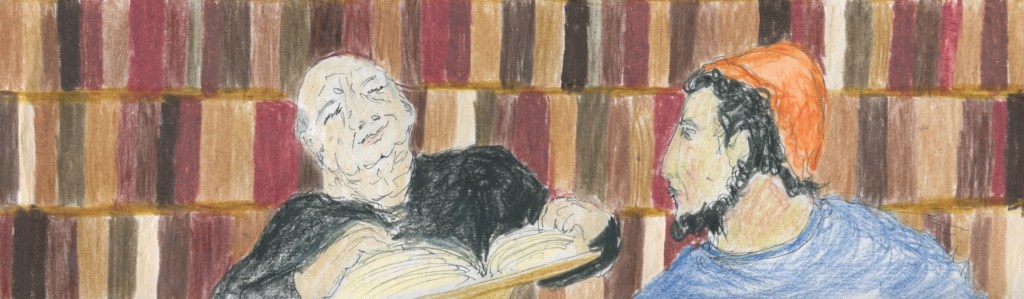

My thoughts stray from Bede’s commentary on the history of Church among the Anglia. He wrote in a room with narrow walls. I was expecting to find in this history of the Lindisfarne the actual beating heart and spiritual energy of the creation of that community. It was stolen from them in the deaths of its monks and burials in the earth with saints sharing their earth space with sinners and this driving love force was overlooked in the history of the politics of rule and obedience.

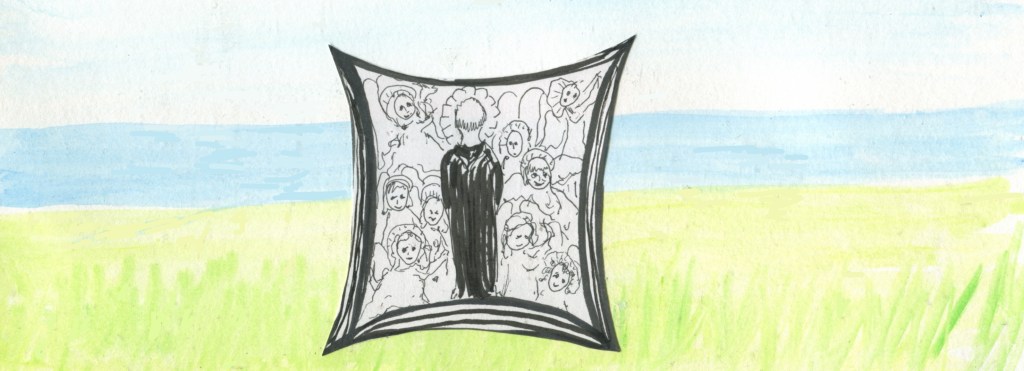

Dear God, is it all vanity to look for you in the closed circles of eternal repetition? Recently I’ve been gathering stones together with the survivors of Lindisfarne. And they were chiseling a gravestone with a raw circle for sun and a raw arc for moon where time is measured against notions of a doomsday. It’s an eternity of wandering paths in a labyrinth, circles within circles and the other way around again, longing for clarity but not for conclusion.

I’ve also been to the casting away. I’ve been to death and back again. In the sorrow lies the promise of joy. In the cruelty of greed, lies the promise of empathy, lifting up the lowly. Time is measured in the repetitious pattern of circles — the tail grabbing. Help me, guide me, release me from the futility of circle into to the vast unknowable eternity of Creative Love. With each circle expanding we find an eternal newness in pattern, restoring, resurrecting from earth stuff to life stuff to unstuffed spirit. Guide me, let me walk the labyrinth free of stagnation that confines imagination. Amen.

Is it a longing or an observation: eschatological time, or the “end times” or “doomsday” or “the seventh and the eighth ages of the world or Word or “Ragnarök” which can never be now. It always must be then, and never visited by the living. If God speaks of it, human discernment of those utterances are as deeply personal and subjective as any mystical encounter. It isn’t actual prophecy. Time in human understanding is linear. Eternity is circular. This is a very ancient wisdom. In time, one thing happens after, or before another. But in a circular pattern of eternity the now is also the then, and maybe it is a present fullness, not so much an after and done kind of event — a circle — the endless tail grab. Always, by its very nature, the eschaton is unknown and unknowable. It is a page un-written.

(Continues tomorrow)