Historical Setting: Jarrow, 793 C.E.

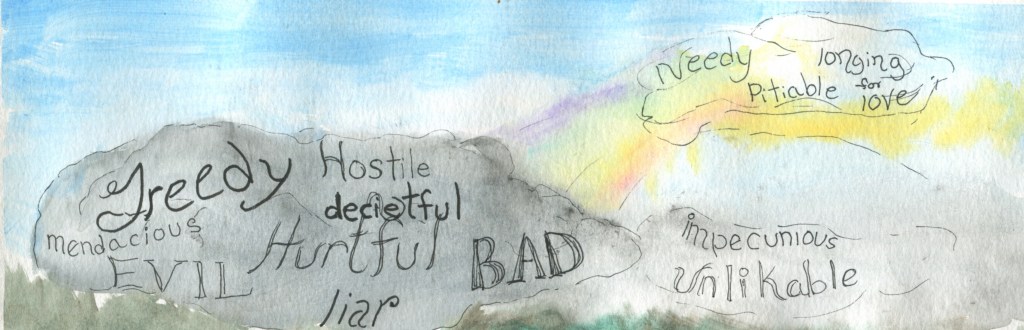

In the water walking allegory, stepping out of the boat is called “faith.” But then the word “faith” was usurped by religion as a uniform requirement for belonging —a shared creed. Back when faith was still raw and personal, Jesus told Peter he needed it. Then by religious use, faith changed its meaning to define the boat — the belonging to a shared religion. But faith is still personal for some water walkers.

Dear God, you know my heart.

I’m one who would drift free or maybe simply sail with the wind. But religion happens when the direction of the wind isn’t trusted and the captain calls for the oars then we all row in unison. It is so Roman, this galley with oars, called religion. But sometimes it takes me where I need to go. When I dress as a monk, I expect the human being at the tiller will steer as God asks of us.

As I read through Bede’s history, Christians are always groping the changing winds with steady oars for uniformity and order.

So it is, when a Synod or a Council gathers within religion and the purpose isn’t to compromise, rather it is called to name a singular order. Even though the Synod of Whitby [footnote] was convened by Hild of the Irish tradition, it was purposed to establish a singular direction or rule. Those who could flex, yielded to those who could not. For the Irish, the side I’m drawn to, the internal, personal relationship with God isn’t by creed or calendar or rule, so on matters of rule the Celts flex. They fall in line with order and uniformity. Some argue, others, like Hild, do whatever we can to hold to the Irish tradition but an inflexible order apparently gives the pope authority over random currents and shifting winds of individual prayer. The Synod of Whitby eventually went along with the pope’s date for Easter and all the sameness implied in that.

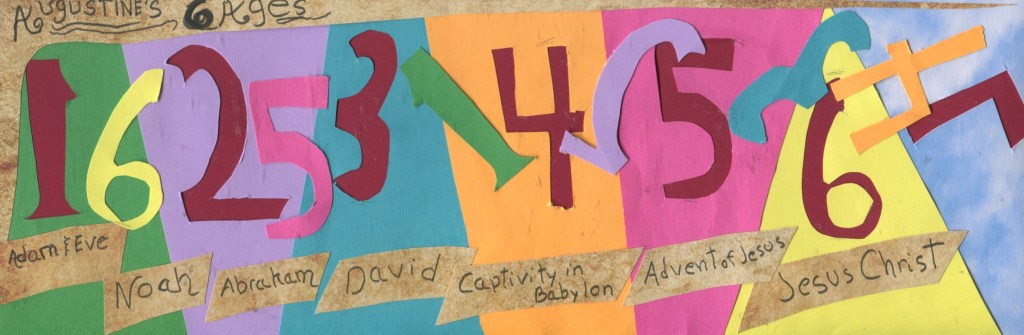

Jarrow wasn’t founded by an Irish bishop so the buildings are of stone, and the style is Roman. It was, after all, Pope Gregory the Great who assigned Augustine and his band of missionaries to bring Christianity to East Anglia in the first place. This history of earlier centuries is well-known here, and it is also recorded by Bede in this history that I still have laid opened on the bookstand. Taking the pope’s side is as old as Christianity for these people.

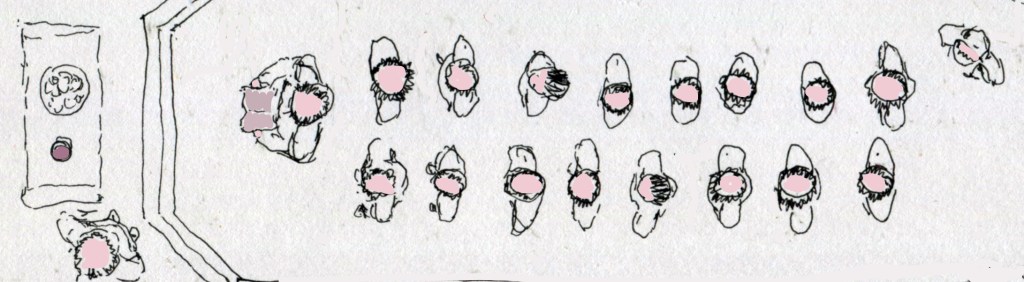

Just now a man signing in at Wilbert’s table is also a layman. And he is asking Wilbert about the attack on Lindisfarne.

[footnote]Synod of Whitby, Chapter 25, p. 153 (Bede The Ecclesiastical History of the English People: The Greater Chronical, Bede’s Letter to Egbert (Oxford press, Edited with an introduction and notes by Judith McClur and Roger Collins. 2008.)

(Continues Tuesday, December 9)